Originally published on January 1, 2025. All data in this article may have been updated since the time of writing.

“If I was ever at a risk of harming myself. That was it.” Brandon Shaw thought he knew what to expect. He had detoxed from heroin and methadone a number of times, but this detox was different.

Shaw spent 14 years on the streets, mainly in Edmonton. During his detox, he couldn’t swallow food and lost the ability to communicate. “I literally thought to myself, am I going to be like this for the rest of my life?” says Shaw.

Shaw’s mother, Angie Staines, exhausted every avenue and every resource available to ensure her son survived. She recalled staying by his side as he went through the turmoil, “And I remember laying there hearing him having night terrors, and he was having focal seizures.”

The pain and suffering of her son left Staines feeling helpless. “At one point, I thought we’d be better off dead. I didn’t know how this [was] gonna end.”

“Everything had been stripped from us,” Staines says, “It was just him and I, and the opiate clinic, and that was it. Of course, we had our friends, but it was — it was very isolating.”

“Watching what he went through in that time changed me as a person.”

Staines’ experiences motivated her to start organizing. A nurse by trade, she began doing direct outreach work to support those living on the streets. She formed the 4B Harm Reduction Society, and now Shaw works with her. They are outreach workers, educators, and harm reduction activists. Shaw eventually regained the ability to eat and speak. With stable housing, he is attending post-secondary and aims to continue helping support community members in need.

Shaw’s story is one of many, a reality for those who are living in the streets of Edmonton.

As a downtown campus, MacEwan University is often a respite for students, faculty, the public, and the unhoused. Now, more than ever, many houseless community members face life without or minimal shelter. Oftentimes, they are forced into isolation.

“When I was on the street, my interactions with society were not very positive and I didn’t find my interactions with the system very uplifting, and I felt very discouraged,” Shaw says.

“So, I just isolated.”

He noticed, however, that he had outreach workers on his side, “When I had no one, I had them.”

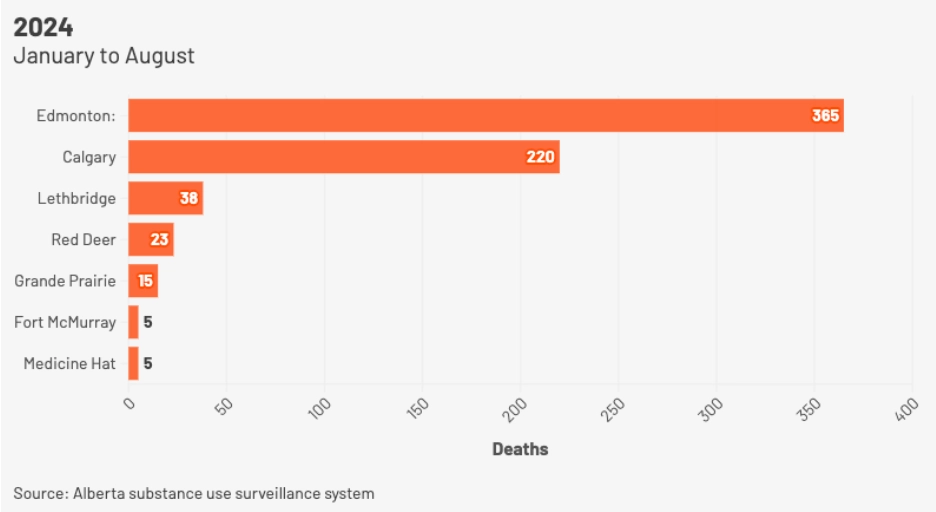

At the time of writing, the Alberta substance use surveillance system shows 671 unintentional drug poisoning deaths in Alberta from January to August of this year. Of those 671 deaths, 365 are in Edmonton. These are stark numbers, especially as some critics say Alberta’s surveillance system undercounts drug poisoning deaths by 25 per cent.

Not all unhoused persons use drugs. However, reports indicate that substance use is more prevalent for those living on the streets. The risk of drug poisoning is far greater for the most marginalized in our communities. In September, a report from Edmonton housing agency, Homeward Trust, found that Edmontonians experiencing houselessness had risen 71 per cent from January — an increase from 2,744 to 4,693 people who are houseless or without stable housing.

Harm Reduction

“I think that there’s probably some misunderstanding from the general public about what harm reduction is and what it’s intended to do,” says Marliss Taylor, the director of Streetworks at Boyle Street Community Services. “So that makes the work a little bit challenging.”

“The shortest definition of harm reduction is keeping people as safe as possible and it doesn’t matter if they are drug users or work in sex trade. It is helping people stay as safe and healthy as possible,” she says.

“Harm reduction looks at both policy and practice and really values the input and leadership, if possible, from the community that’s most affected,” Taylor says.

For Staines, harm reduction is more than clean supplies — it’s about connection, autonomy, and standing together with the most marginalized.

“You hear people say harm reduction is meeting people where they’re at,” Staines continued, “It’s standing with people and hearing their stories. Listening to those stories of trauma and helping them jump through the hoops that the system has put in place to keep these people down, to keep the community down.”

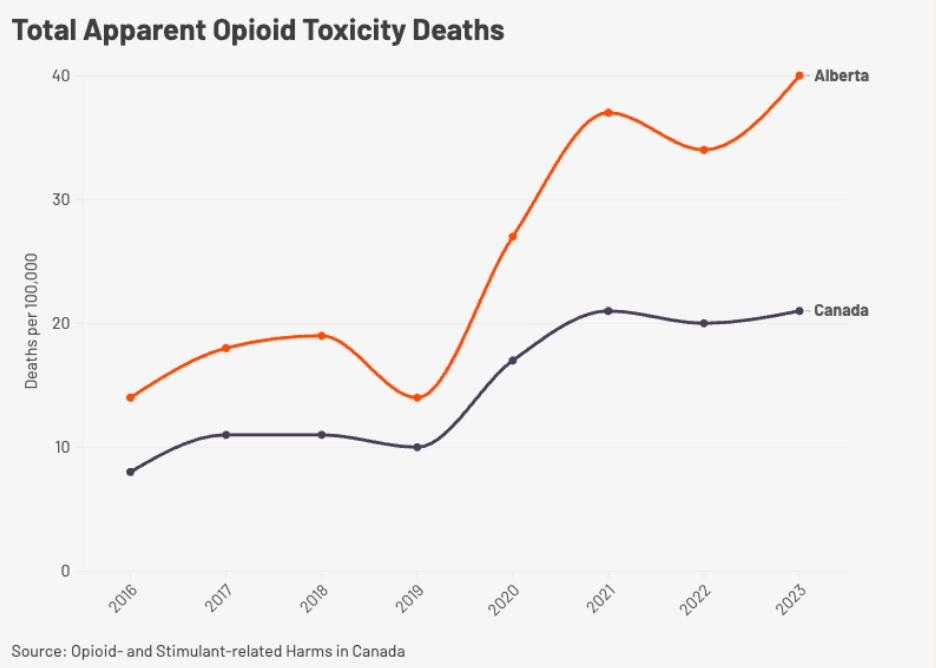

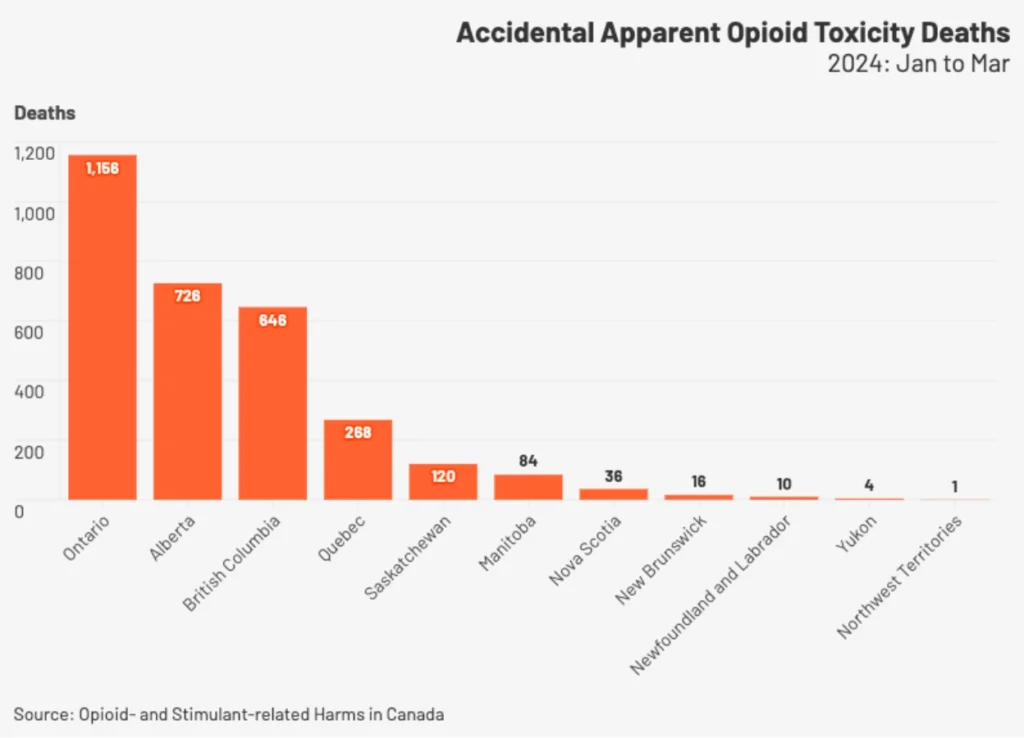

According to the Public Health Agency of Canada, from January to March of this year, 84 per cent of accidental opioid deaths occurred in B.C., Alberta, and Ontario. 81 per cent of all accidental opioid deaths in 2024 involved fentanyl, and 84 per cent involved non-pharmaceutical opioids.

In response to the rising amount of deaths and drug poisonings, The UCP government began to implement Recovery Alberta, an organization that’s “charged with delivering mental health and addictions services.” Recovery Alberta takes a recovery-oriented approach, which emphasizes access to treatment and recovery supports and less focus on harm reduction.

“If you look, they have AHS providing safer use supplies in the past, and I want to make that very clear, all of that is on the line now,” says Staines.

“Things like our safer use supplies are under fire. Grants are not being renewed. These are things that improve people’s health outcomes.”

Staines argues that harm reduction and recovery must work together in the larger conversation around drug policy. “Recovery is not linear, and harm reduction gives people the autonomy to make the choices that are right for them,” says Staines.

“Harm reduction is what is keeping people alive while they are waiting to get into treatment,” says Shaw.

Taylor says there is a spectrum of services for vulnerable people and hopes that harm reduction has a space within the spectrum. She also noted that harm reduction can often be a path towards recovery.

Josh Dillon, MacEwan’s little-known campus navigator, doesn’t know how things are going to look for harm reduction efforts with Alberta’s new recovery model but believes harm reduction is a way to mitigate the risks and dangers to the community that they’re responding to.

Dillion works alongside MacEwan’s security services and is from the Mustard Seed, a Christian non-profit group that has cared for people experiencing homelessness and poverty since 1984. A security spokesperson told the Griff they hope to get “another Josh” for next year.

As MacEwan’s campus navigator, Dillon carries out wellness checks — situations and calls for service where there’s not an observable threat or reason for security — and provides community members with water, granola bars (the most common), and jackets or toques if they need or want them. “I’ll talk to them, explain that I’m with Mustard Seed, which honestly helps a lot,” he says.

Sydney Bennell, co-founder of the Coalition for Harm Reduction at MacEwan (CHARM), wrote in an email to the Griff that “We are unsure what the future applications will look like and can’t speak about the nature of the recovery model and its impact on CHARM.”

Bennell, a registered nurse, worked with registered social worker Sarah Stone and other community partners to help create CHARM at MacEwan in 2018. Bennell told the Griff that CHARM is funded until 2025 by the Community Capacity Building Grant from AHS (now Recovery Alberta, which is not a part of AHS).

For Dillon, fentanyl is the main concern for harm reduction, and naloxone is a regular part of the job. “I can’t imagine doing this job without naloxone,” he says, “I don’t think [we] would be doing our jobs properly if we weren’t able to respond in that aspect,”

“It’s so key to having harm reduction.”

“So, with that being said, it’s been used a lot. I’ve used it multiple times having it from February. I mean, in the last month, there’s been two people that have been reversed from opioid poisonings.”

While security does not have an official tracking, Dillon told the Griff they have administered Naloxone five times since they started carrying it earlier this year. They were also present for two other opioid poisonings where others administered Naloxone.

“It’s true. Harm reduction works,” Dillon says. “I mean, that’s what the studies show, that’s what the science shows.”

Bennell said CHARM adapts its priorities for education and advocacy efforts depending on trends. She said CHARM has done “harm reduction-themed workshops, webinars, and e-modules,” helped MacEwan’s security services implement harm reduction and naloxone training, and provided in-class and department training, among other things.

CHARM’s work and activities, Bennell says, are accessible to all MacEwan students and employees through Meskanas. While CHARM builds awareness through education and training, it does not provide direct harm reduction services.

Recommendations

Shaw agrees that CHARM is a positive step towards implementing harm reduction on campus. However, he recommends listening and getting feedback from people with lived experience. “Are they asking the community what we can do as an organization? Because it’s not just enough to assume, ‘Hey, we’re gonna bring resources, and we’re just gonna help people.’”

As institutions like MacEwan grapple with the complexities of drug use and uncertainty from shifting drug policies, Staines emphasizes the importance of learning with empathy.

“Understand how we got here. Understand that spectrum of [drug] use. Also understand reconciliation and hear people’s stories.”

Taylor hopes that people will become trained in using naloxone and carrying kits around.

She understands that it is a lot of work to give out clothing and supplies and says it would be wonderful if universities had cold-weather clothing drives to give to the Bissell Centre and other places that do that work.

“But, people do need to have some of those supplies, or just doing some fundraising,” she said.

Staines doesn’t expect everyone to go out to do outreach services, but she hopes students read more on the subject of harm reduction, have conversations, and get involved somehow. “Start learning about harm reduction — but from drug users groups. Build those programs with the voices of people who use drugs.”

“And you know what? Try looking people in the eye when you walk by them.”

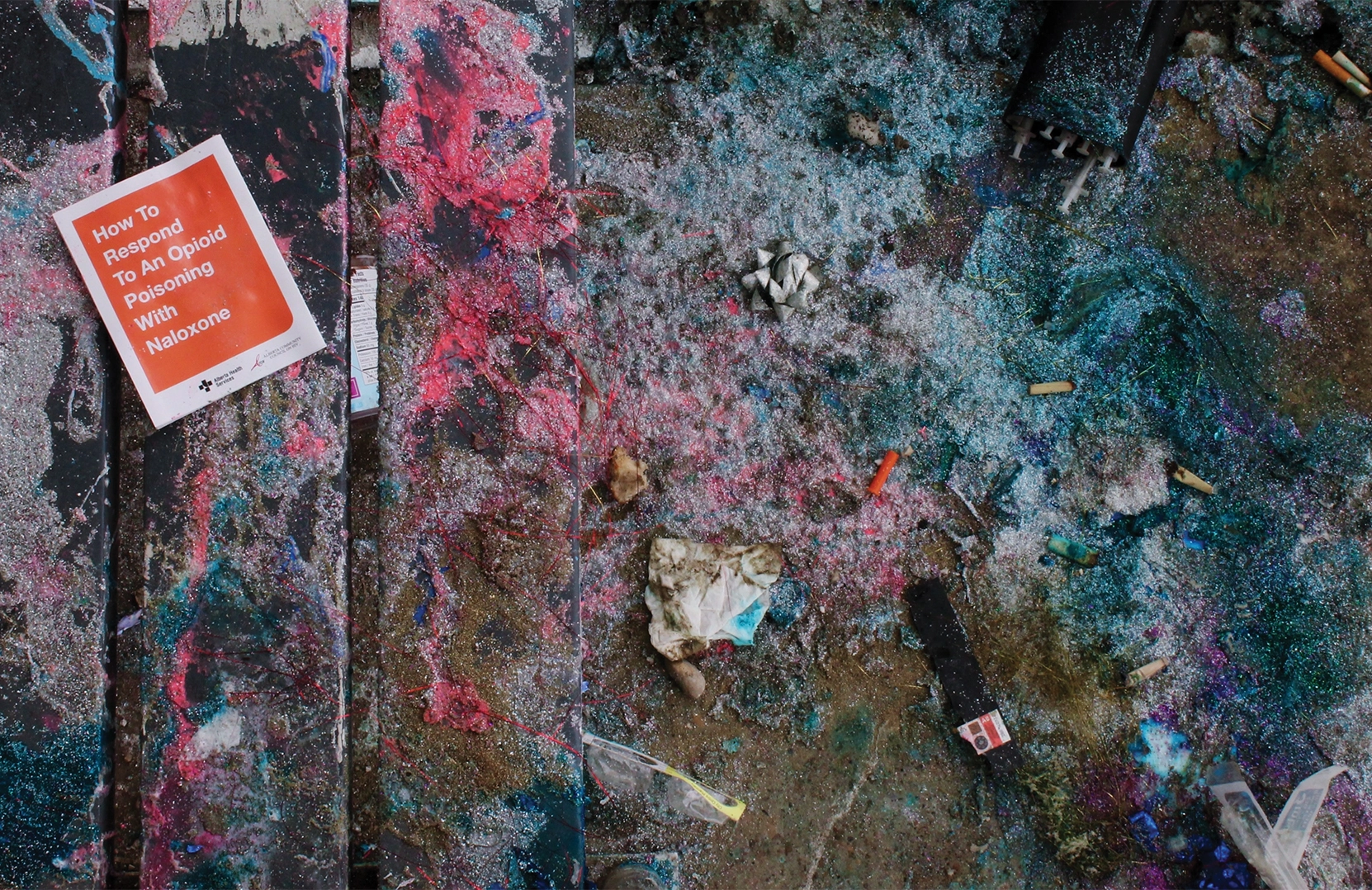

Photo by Amanda Erickson

0 Comments