There were zero female directors nominated at the 2020 Oscars. But it’s needless to say that women have been long underrepresented in the film and television industry — directors and actors alike. According to the Center for the Study of Women in Television & Film, in the top 100 grossing films of 2019, women represented: 12 per cent of directors, 20 per cent of writers, two per cent of cinematographers, 26 per cent of producers, 19 per cent of executive producers, and 23 per cent of editors.

It could be argued that these statistics reflect the fact that women create films very differently than their male counterparts. One possible factor as to why is film critic Laura Mulvey’s theory of the ‘male gaze’ — the act of depicting women, in the visual arts and in literature, from a masculine, heterosexual perspective that presents and represents them as sexual objects for the pleasure of the male viewer. An example of this is the contrast in the depiction of the character Harley Quinn in Suicide Squad, directed by David Ayer, to her character in director Cathy Yan’s Birds of Prey.

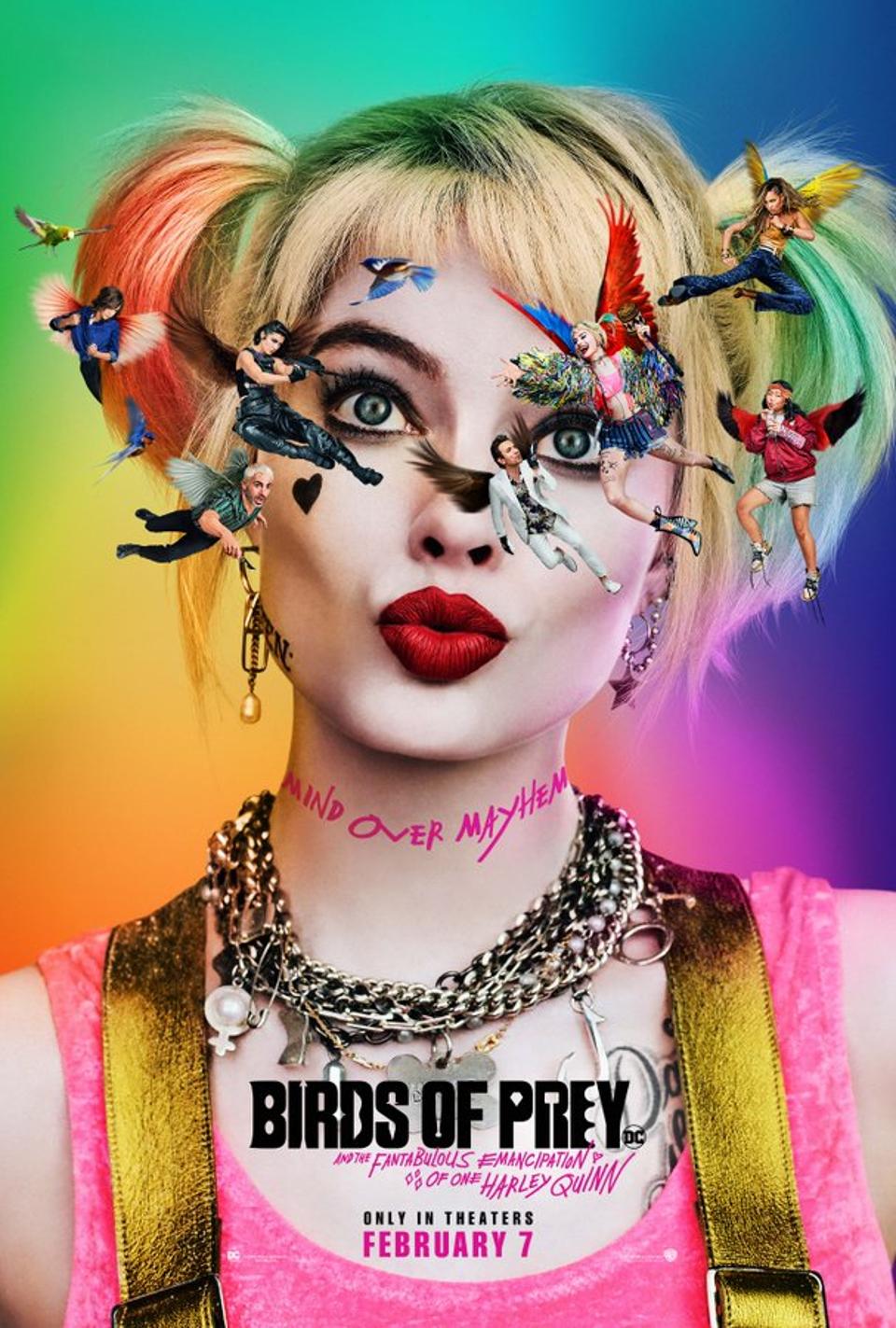

Based on the comic book series by DC, Birds of Prey (And The Fantabulous Emancipation of One Harley Quinn) screams female representation, from screenwriter Christina Hodson to star and producer Margot Robbie. What makes this film different is not just the story itself but how it’s told; it’s fully aware of the male gaze and criticizes it. How? Well, looking back at Suicide Squad, Harley Quinn’s main purpose was to provide sex appeal. From the character’s seductive introduction where she is hanging in her cage, all the way to her skimpy outfit consisting of a torn “Daddy’s Lil Monster” shirt, bikini-style booty shorts and fishnet stockings, a heavily padded bra to accentuate her chest, pigtails long enough to “pull on,” and a choker — with the nickname of her ex, the Joker — that has an uncanny resemblance to a dog collar. She oozed sex while fully personifying the disturbing trope of the “crazy hot chick.” You know the one — men fantasize about her, they dream of controlling her. In the spin-off, however, she’s no longer externally and internally suffering from a perverted male ideal of who she should be and what she should look like. With her shorter pigtails accompanied by choppy bangs, a cropped jacket with confetti tassels, bright suspenders, and a free-spirited attitude, Harley certainly looks and feels emancipated.

Nevertheless, Birds of Prey definitely has its share of sex appeal. Harley is just as alluring licking a lollipop and twirling with a drink in hand, and at least one of her outfits shows as much skin as her signature one in Suicide Squad did. But the difference in her depictions in Birds of Prey are as follows: she looks like she actually dressed herself and had fun with it; it feels like she’s choosing to be sexy, she’s an active participant in the seduction and not just a victim of it; and how she’s captured by the camera. In Suicide Squad, Ayer lingered on specific body parts (mainly her chest), with an angle that suggested a specific power dynamic; one that was sleazy and, more times than not, predatory.

Birds of Prey was aware of its origin that overwhelmingly and, perhaps, intentionally objectified women. However, it worked to combat factors of the male gaze by directly engaging with that troubled history. It used subtle yet thoughtful details to reinforce the concept of Harley’s self-ownership. She’s not just an object to be gawked at.

The truth is then exemplified — in her own handwriting — directly in the title.

0 Comments