It was the mid-1930s when zines got their official start in the form of science fiction fanzines. According to Julie Barel in her 2003 article “The Salt Lake City Public Library Zine Collection”, zine history is extensive, but “their strongest historical connection, however, is with the science fiction fanzines of the 1930s, in which fans kept beloved serials and characters alive by writing their own stories,” explains Baron. A desire for self-publication surfaced underneath the mass production of mainstream media, and a fascination towards science fiction led to a subculture of fans who wanted to create something for themselves, by themselves.

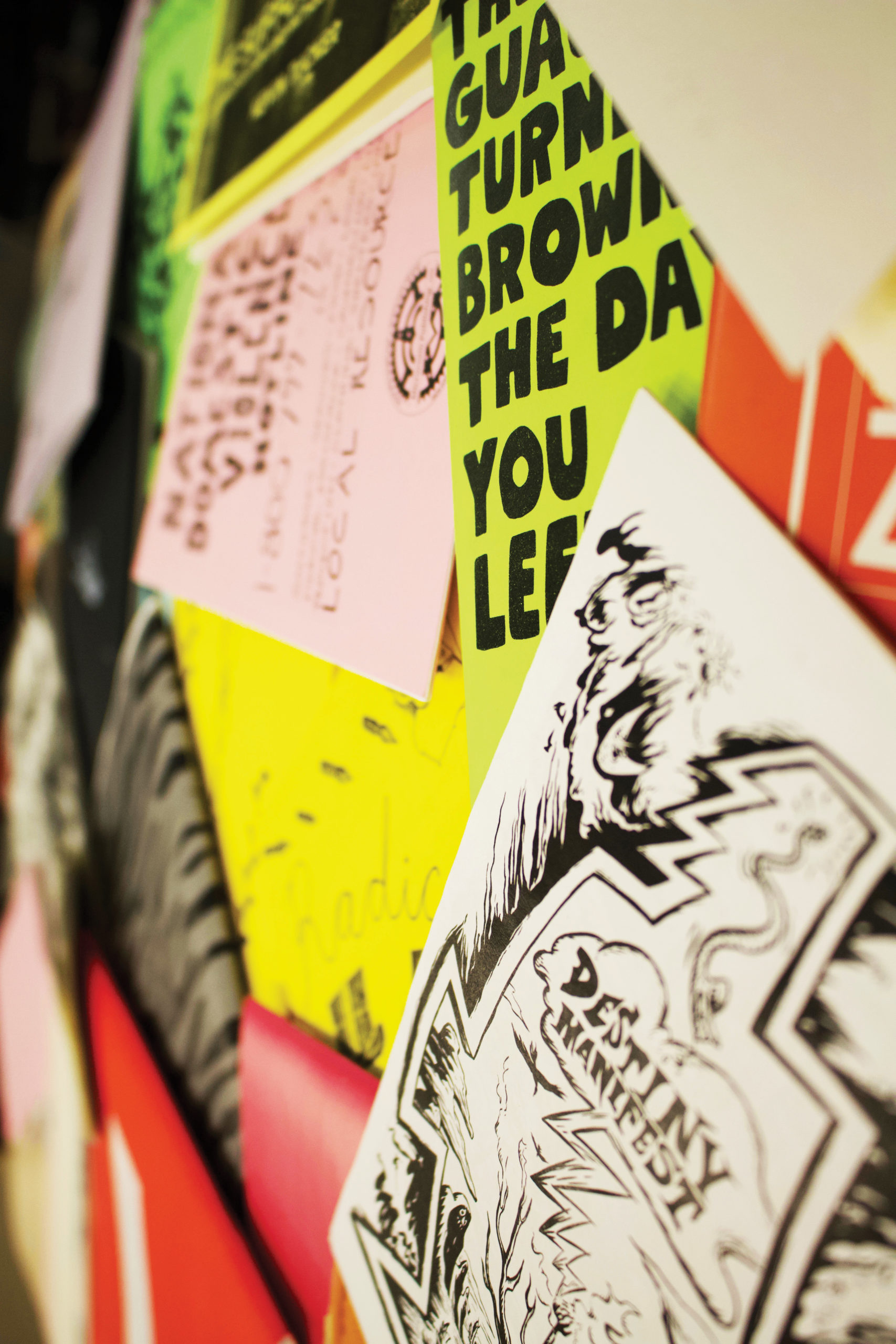

In the 2018 article “Writing as Making: Introduction to Zines,” Kristin Fontichiaro offers a general definition of the medium: “zines are small, handmade magazines — with pages commonly 4.25’’ x 5.5’’, a folded half-sheet of copy paper — that reflect topics or themes of significance to the creator.”

Pronounced “zeen” and short for magazine, zines have almost always belonged to niche subcultures throughout history. The 1970s saw a shift in fanzines from science fiction material to zines dedicated to independent music. By the ‘90s and early 2000s, zines were a staple in the “Riot Grrrl” movement, which was led by women who persued social change through alternative art and punk music.

In Edmonton, zine distributor Amy Leigh says she became involved in zines thanks to the ‘90s punk-feminist subculture. “My interest in zines definitely came through DIY and independent music, and the Riot Girrrl movement,” says Leigh. “That was what really hooked me into zines in the first place, people like me writing zines about their lives or how, you know, they felt like outcasts or weirdos, and I think since then it’s gotten a lot deeper and beyond that.”

Leigh explains that she has been involved with zine culture for about two decades now, and in 2017, she adopted the Zine Machine Project in Edmonton. “It’s an old snack vending machine that has been repurposed to distribute small hand-sized zines,” says Leigh. Formally known as “780 Distro,” the repurposed 1980s vending machine has taken on a new life by selling zines from around the world.

Initially, the Zine Machine Project made its appearance at Transcend Café in Garneau in 2014. But it was moved into Allard Hall at MacEwan in March of 2018, where Leigh used it as an art installation project during her time as a student in the Arts and Culture program.

“Instead of writing a research paper, I asked if I could do an art installation, so I did a zine making workshop and the people who made the zines in that workshop had their zines in the machine for two weeks,” says Leigh. “I would sometimes just watch and see how people interacted with the machine. A lot of people were like ‘what is this?’”

Zines generate a curiosity that almost parallels the same interest one might have towards reading someone else’s diary or flipping through an artist’s scrapbook. For decades, the medium has allowed anyone the ability to create a tangible piece of their own story without having to worry about the economic or social pressures of mainstream publishing.

Anyone can create a zine, and accessibility is what has allowed them to become the unique form of media they continue to be.

“The awesome thing about zines is that anyone can make them, they can be about whatever you want and they can look however you want. So that makes it a very accessible form of making media or sharing stories or thoughts, which in turn I think is a really great tool to create community,” explains Leigh.

She also says that while she is involved with zine culture in just about every way, she doesn’t make her own. Leigh emphasizes her interest in supporting others. “I really enjoy cheerleading or championing other people’s work. As a white woman I think it’s really important to step back and help amplify marginalized voices as opposed to taking up that space,” says Leigh.

But, she reiterates that zines can be created by anyone who wants to make one. “While I am continuously trying to encourage marginalized voices to make zines, zines don’t exist specifically for one demographic. But I think it’s really great way for people whose voices are not normally heard to share their stories and their art,” she adds.

The idea of self-publishing might seem daunting, but, since the restrictions for zine making are almost non-existent, it’s no surprise that zines are the format of choice for those who want to create without boundaries. Generally, the only limit zines have is their not-for-profit nature, which in Leigh’s opinion “blows open the door of what you can do with zines as a medium.”

As for the Zine Machine Project, it has to conform to its manual functions, meaning that prices cannot be programmed and that all the zines within the machine are sold for $1.50. With that, Leigh explains that the zine makers receive a dollar off of each zine while the project keeps the remaining 50 cents to keep it running.

“In general, with zine distribution or the reselling of zines, usually the wholesale retail split is like 40/60 or 50/50,” explains Leigh. “In my experience, generally people sell zines for the cost of what it cost to make one. I don’t think anyone’s really making a huge profit.”

Along with the Zine Machine Project, Edmonton has been celebrating zine makers and zine enthusiasts at the Edmonton Zine Fair. In December of 2018, Clean Up Your Act Productions (an Edmonton-based music promotion company) hosted the 10th Zine Fair alongside the Edmonton Public Library.

Leigh also admires the variety of craft displayed at Edmonton’s zine fairs, “I think they’re really interesting because there are people who are making paper zines but then there are people who are doing adjacent things like making patches or buttons.”

Whatever form it might come in, it seems as though the DIY nature of zines is welcomed in the city. If you’ve never seen a zine before, you can even check out a variety on the library stands at MacEwan.

In the next year, Leigh plans to line up a few places to house the Zine Machine Project, and hopes that it can find a home in free public spaces. She believes it’s important for people to have open access to it, and to the art of making zines.

“For any kind of subculture in Edmonton, if you want something cool to happen you have to make it happen. It isn’t kind of just handed to you or it doesn’t always already exist, and that’s a thing I really love about this city,” says Leigh. “I think that’s what helps sustain doing independent creative projects like DIY or punk or whatever subculture, zines being one of them.”

Photography supplied & by Sydney Upright.

0 Comments