Dating apps have become the paramount vehicle for meeting new people, whether it be for a date, a hook-up, or a quick ego boost. As of 2014, the popular dating app Tinder has over 50 million users, with an average of 1 billion swipes and 12 million matches a day, according to The New York Times. Little did I know when I decided to use Bumble, branded as a feminist dating app, I would become the victim of truly frightening harassment.

It started innocently enough: a swipe right, a match, and then, a difference of opinion. He quickly turned a debate of current events into a verbal assault, twisting my words and insulting me. The man became increasingly aggressive to the point where I felt it was time to unmatch. He was not satisfied with this decision.

He sought me out on all forms of social media, somehow finding me with only a photo and my first name. Despite my efforts to block him, he found me again —- each time with an angrier, more aggressive message than the one before. He alternated between belittling me, complimenting me, insulting me, and asking me out on a date — a manipulative tactic most women are all too familiar with. I was forced to switch between combating his insults and appeasing him with compliments to avoid further angering him. This contact went on for just over two months. My workplace was listed on my social media — when words typed on a keyboard failed, would he come to confront me in person? According to a 2018 report by Statistics Canada, technology has changed the way people are being stalked. Stalking incidents have decreased from nine per cent to six per cent; however, more people are receiving unwanted emails and messages through social media, which represents 28 per cent of all forms of stalking.

Thankfully, I was eventually able to block his efforts to contact me online, Bumble successfully banned him from the app, and he never pursued contact in person. But what if he had? What would I do? For many women, efforts to block their harassers are met with violence.

To my Bumble stalker, and many men like him, the word “no” is not taken at face value. To them, “no” means “convince me.” He was under the impression that my initial swipe right meant that he was owed something — a date, my time, my understanding. He is not alone in this sense of entitlement.

Criminal harassment is legally defined, according to Justice Canada, as “ (a) repeatedly following from place to place the person or anyone known to them; (b) repeatedly communicating with, either directly or indirectly, the person or anyone known to them; (c) besetting or watching the dwelling-house, or place where the person, or anyone known to them, resides, works, carries on business or happens to be; or (d) engaging in threatening conduct directed at the person or any member of their family.”

Stalking is classified as criminal harassment in Canada, and a staggering 58 per cent of Canadian women have been stalked by a former partner, with women making up 76 per cent of all criminal harassment victims, according to Statistics Canada. Of these victims, one-third of cases resulted in violence. Homicide is now the fifth leading cause of death in women under 45 with more than half of these deaths being committed by a former partner, according to the CDC.

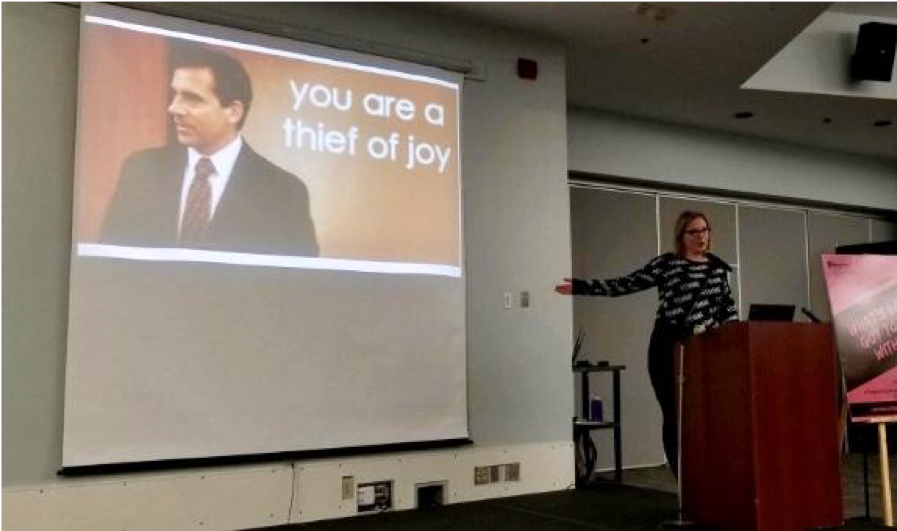

On Feb. 12, 2019 Julie Lalonde, self-described feminist buzzkill and stalking survivor, travelled to MacEwan University from Ottawa to discuss stalking and unhealthy relationship dynamics.

Lalonde revealed her 10-year-long stalking ordeal in which her former partner bounced between sending her love letters and sending her threats. The torment that began at the age of 18 with a two-year-long toxic relationship, did not end until she was 30 years old.

Lalonde was good friends with her would-be stalker throughout high school. When she broke up with her high school boyfriend, he seized the opportunity to confess his feelings for her. He suggested his kindness meant he was owed, at the very least, a short relationship. Lalonde began a two-year relationship that eventually became toxic. Upon finding the courage and support to leave him, 10 years of constant stalking began. He left notes and gifts, came to her home uninvited, wrote her letters, and tracked her day-to-day activities. When she moved, he found her. It was relentless.

Her ordeal only ended with his death.

Tragically, Lalonde’s stalker died in a car accident. While she never wished for his death, it allowed her the freedom to speak out about the dark reality she had experienced for a decade.

Criminal harassment is an incredibly taboo subject, as the majority of victims do not feel they are in a safe position to speak out. Lalonde expressed, “If you are waiting for a ‘Me Too’ movement for stalking, it’s never going to happen.”

Donning a pair of bright pink stilettos and a black knit sweater emblazoned with the word “femme,” Lalonde shared her story with us in an attempt to alleviate the stigma around criminal harassment and to offer preventative tips.

The major takeaway from Lalonde’s presentation is that stalking and unhealthy relationship dynamics are a direct result of the way men are socialized to handle rejection and the way society has come to view romance. Several famous romantic comedies include problematic examples of criminal harassment — stories of unrequited love remedied by grand gestures.

Take, for example, the wildly popular young adult novel-turned-film Twilight, in which sparkly vampire Edward regularly watches Bella sleep without her knowledge or consent. It is framed as romantic; he is so drawn to her and so wants to protect her that he can’t help himself. Remove the sparkle and the soundtrack, and you have an older man watching an underaged girl sleep. At their core, many romantic comedies perpetuate similarly problematic romantic ideals. The Christmas classic Love, Actually romanticizes the obsession best man Mark has with his best friend’s bride Juliet, while When Harry Met Sally perpetuates the idea that men and women cannot be just friends.

“Respecting boundaries is romantic,” Lalonde quipped.

Beyond the skewed ideas of romance sold to us by Hollywood, criminal harassment statistics are further evidence that men are not taught to handle rejection healthily. “Men have so few tools in their emotional toolbox,” Lalonde said, “if you’re only equipped with a hammer, if your only emotional tool is anger, that’s a problem.”

A common behavioural thread in stalkers and abusers is their ability to manipulate, to feed off of the victim’s empathy. Lalonde’s stalker regularly threatened to harm himself. My cyber-stalker would alternate between compliments and insults, appealing to my intelligence moments before calling me a bitch. There is a common misconception that only certain women are victim to abuse — weak or meek women. The reality is that a true manipulator can manipulate anyone. The message Lalonde sends through her story: you are not responsible for the conditions someone else sets, nor are you responsible for their actions.

Despite the overwhelming statistics, Lalonde is hopeful the next generation of men can have better emotional tools in their toolboxes. Her advice to parents is to raise empathetic young men, teaching men how to handle rejection and re-adjust their sense of entitlement.

An example can be found in a viral conversation posted on Twitter in which an aunt noted her nephew was sad about a girl in his class rejecting him. When she asked, “You know what you have to do right?” he responded, “I know, I have to keep trying.” “No,” she responded, “If she said no, it means no.”

“Respecting boundaries is romantic.”

— Julie Lalonde

Lalonde also suggests we tackle the friend-zone myth — the belief that men are owed a relationship or sex in exchange for kindness. In reality, women do not owe anyone affection, no matter how kindly you treat them. The friend-zone myth is popular in involuntary celibates, or incels, a culture built around male entitlement. Members of the online sub-culture claim they are unable to find romantic or sexual partners. At least four mass-murders, resulting in 45 deaths in North America, have been committed by those who described themselves as incels, according to The New York Times.

Lastly, Lalonde recommends that young women prioritize being safe over being nice, learn to recognize manipulation, and demand more of our institutions. We must also be aware of our language, and the ways we may unintentionally trivialize stalking. When we joke about “stalking” our friends on Facebook, it minimizes the experiences of those being cyber-stalked and other victims of criminal harassment.

To victims of criminal harassment, both Lalonde and local law enforcement recommend documenting text messages, phone calls, and letters whenever possible as evidence is key in taking legal action.

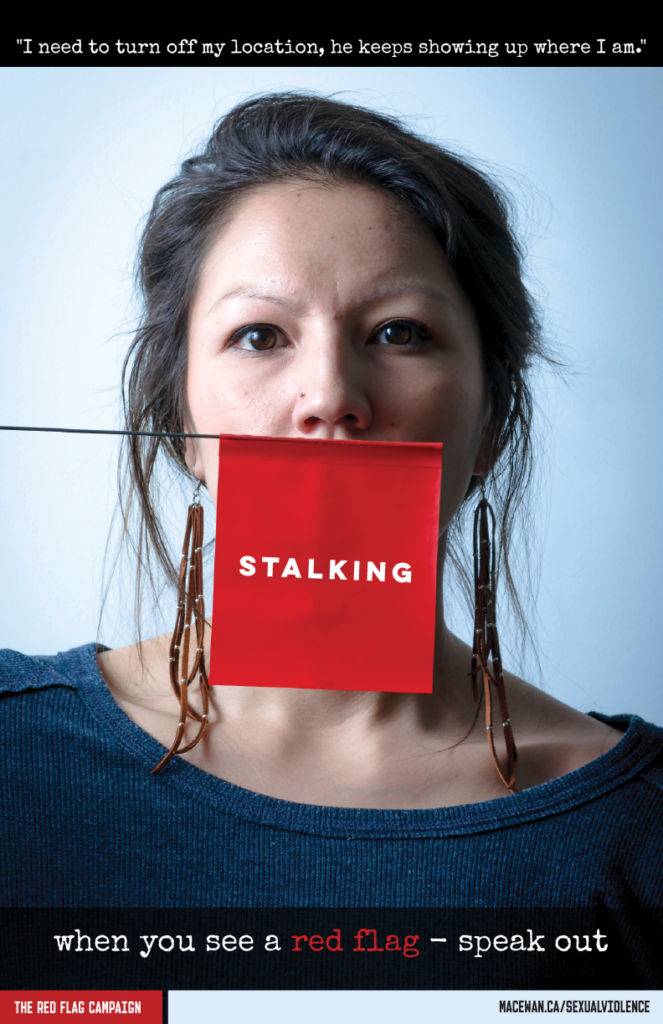

Lalonde’s presentation was part the Red Flag Campaign, hosted by the Office of Sexual Violence Prevention, Education and Response. If you or someone you know is struggling through unhealthy relationship dynamics, or criminal harassment, the MacEwan Anti-Violence Education Network (MAVEN) website states that “MacEwan University’s Sexual Violence Response Coordinator, together with the Sexual Violence Response Team, can refer you to counselling services, coordinate academic or workplace modifications and help you understand the reporting options available to you.”

Photos and graphics contributed by Milo Knauer, Jennifer Hamilton, and supplied.

0 Comments