Downtown Edmonton has become an increasingly vibrant community. Rogers Place is just the latest revitalizing tool meant to transform the city centre into a world-class area for Edmontonians to enjoy.

But this downtown transformation has not come without pushback. Some of Edmonton’s most vulnerable communities live in the downtown area, and many people are worried new developments will displace these populations — particularly the homeless population.

According to an article on the Boyle Street Community Services website, “In many cities across North America, downtown revitalization often means gentrification and gentrification means poor people who don’t fit in are moved on to corners of the city away from the mainstream.”

Statistics provided by Homeward Trust Edmonton in 2014 show there are more than 2,300 homeless people in Edmonton. Many are situated in the downtown area, as it is one of the busiest and most accessible parts of the city.

A rare perspective

Peter Hapchyn is a person who was once homeless. He was sitting in the back of a Starbucks alone. Unlike everyone surrounding him, he wasn’t playing around on his phone, nor was he fidgeting as he waits. He was sitting tranquilly, staring at the coffee mug in front of him.

Hapchyn has fluffy blonde hair that’s starting to thin and a pair of big blue eyes. A light smell of cigarettes surrounded him. A pack of Pall Mall cigarettes rested in the breast pocket of his blue flannel shirt.

For a time, he lived on the streets of Toronto as a beggar in the early ‘90s. He has also been dealing with schizoaffective disorder for 26 years, something that has given him no end of trouble. His mental illness was a direct factor leading to his living on the street.

“Living as a bum was a very valuable experience; I don’t regret it,” he says. “That was the most enriching experience I’ve had, and most people would say ‘God, you’ve lived homeless, and you slept on park benches and begged to feed yourself. How could that be enriching?’”

For Hapchyn, the answer to that question is perspective. “To me it was an experience in life that opened my eyes to that aspect, so I walk by a beggar (and) I see him for what he is. I know the life and what it’s about.”

Authorship

Hapchyn spent the past nine years working on a series of books, where he writes about a variety of subjects, from man’s relationship with nature to the promotion of the adventurous and nomadic lifestyle. All three of his books are online and can be found for free on his WordPress, where he hopes he’ll be able to reach out to anyone interested enough to read them.

The stories that have come to him the most naturally, though, are those he’s written about his time as a member of Canada’s homeless population. All three of the books have been published through a vanity press, meaning Hapchyn funded them himself. He’s been able to draw from a lifetime of experiences, including travelling around the Mediterranean Sea on a bicycle trip and living homeless on the streets.

Hapchyn’s most recent book is called The Concise Bohemian Philosophy, a book where Hapchyn describes bohemianism. To him, a bohemian can be defined as somebody that has untraditional social habits and mannerisms.

Hapchyn describes the well-trodden path many are encouraged to go down as a series of milestones, or boxes to check off on a list. “You get out of school, you go to university, you get a job, you marry, you have a family, you do your 40 hours a week, you go to Mexico … the whole material trip,” he says.

Within the group of worldly wanderers, Hapchyn says there are various subgroups in the form of “vagabond young guys that are on the street corner busking, and others who are artists, others who café-bounce.”

By café-bouncing, he refers to the way some will kick around from coffee shop to coffee shop, something Hapchyn does himself.

He says most of the bohemian crowd is younger people who will eventually adapt to the habits and paths one might consider more traditional.

Another one of his works is a collection of essays called It’s a Bum’s Life. It’s through this exploration of homelessness that he hopes to change Canadian society’s perception of homeless people as “lazy” and “indolent bums.”

Looking at things differently

Now that Hapchyn is off the streets, he has a better understanding of the homeless and the struggles they face. Canadians should try our best to face homelessness up front, he says, casting away the “out of sight, out of mind” policy he believes Canada has with its displaced members.

Living as a bum was a very valuable experience; I don’t regret it.

Peter Hapchyn

Homelessness is not the only issue Hapchyn believes most people in the West are too frightened or uncomfortable to speak about. As he said, mental illness is also something that has affected his life in a very personal and adverse way, in no small part due to lack of awareness about his own growing problems at a critical time.

He recalls a rocky trip to India, where he was aggressively pushed into a religion by a group of Buddhists. “That was the first downturn. When I returned from India, it’s like I came back a changed man. I wasn’t myself psychologically. I turned quite negative,” he says.

His parents also recognized a change in their son’s behaviour, and it ultimately affected their relationship. “We had a falling out. I thought they were meddling in my life where they shouldn’t, and that they were too intrusive into my life in that regard,” he says.

“They wanted me to get help, and I was resistant.”

Yet even when Hapchyn did make the realization that he was unwell, he was unable to obtain welfare due to not having a stable address. “I couldn’t get a welfare cheque to get a room, and I didn’t have the money to get a room to get a welfare cheque,” he explains.

This meant he was left on the streets with no plausible means of rectifying his situation, but this proved to be a difficult task. “My condition worsened in a huge way,” he says. “I went way downhill.”

Hapchyn becomes a little sombre when recalling these events. After panhandling for six months in Toronto, his sister found him. It was then he finally received the help he needed.

Long before losing his ability to work due to his illness, Hapchyn worked as a psychiatric aid, and during this time, he noticed certain patterns emerging in the way North American medicine treats disorders of the mind.

“When they talk mental illness, and they say schizophrenia is just an imbalance of your neurons in your brain, and that’s all they have to say for it, (it’s) completely bizarre,” he says.

Hapchyn says this is an incredibly narrow-minded definition of what mental illness is, and he argues such an approach can even be damaging to the path of recovery for a mentally troubled individual. Just like with any other debilitating illness, serious mental conditions come with a loss of will.

“I thought, because of the lack of motivation, that I had a physical illness. That’s how I felt.”

At the end of the day, Hapchyn expresses disappointment at the way the people around him view mental illness and homelessness. “A lot of people are hurting, and I wonder, “What this is here that we’re not dealing with?’”

The Homeless Hub may have an answer to that question, and discusses a possible solution in the report’s conclusion. “We need to shift from a focus on managing the problem (through over-reliance on emergency services and supports) to a strategy that emphasizes prevention and, for those who do become homeless, to move them quickly into housing with necessary supports.”

Hapchyn’s final words on the matter offer a simple solution, because of how he himself managed to move away from park benches and panhandling.

“Get them off the streets. Get them a welfare cheque,” he says. “A little room in a house is all you need to be comfortable.” He believes if they have these amenities available to them, “then they can deal with whatever issues they’re suffering from.”

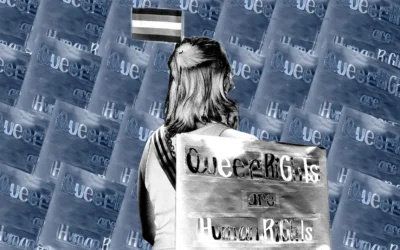

Cover photo by Matthew Jacula.

0 Comments